The Section on Legislation and Law of the Political Process provides for the development and sharing of research, teaching methods, and materials in legislation, legislative process, legislative drafting, the courts-Congress relationship, and interpretation.

Chair: Ryan D. Doerfler, The University of Chicago, The Law School

Chair-Elect: Bijal Shah, University of Arizona Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

RD: Legislation is my main area of research, so it made sense for me to be involved with the section. Some colleagues of mine had taken leadership positions with the section in the past, and they encouraged me to join them. Most directly, Maggie Blackhawk, who is a good friend and former colleague, encouraged me to follow her as chair. She is now emeritus chair of the section.

BS: I research and write in administrative law and legislation. I am interested, in particular, in the impact of Congress on the administrative state. I have always enjoyed the section’s programming at the Annual Meeting, and I have great respect for the committee, which consists of brilliant and diverse scholars. When Maggie Blackhawk asked me to join the committee and to consider being the chair-elect and then chair, I said “yes” because of the terrific group of people that spearhead the section.

RD: We have an executive committee that consists of six people, and there is a chair and chair-elect. The emeritus chair usually participates in an advisory capacity. It is a pretty small set of people in our leadership. In addition, we also administer the New Voices Program, which is a panel at the AALS Annual Meeting where junior scholars in legislation will present papers and have senior scholars comment on them. This year’s program was done with the Administrative Law Section. We have an additional person who helps us coordinate that program who works in coordination with the executive committee.

BS: Our fairly simple leadership structure makes it easy and enjoyable to collaborate. We all make decisions jointly and all have a say in the process of planning the Annual Meeting programming, although the chair takes a lead role in planning the program. In addition, I think the small size of the committee helps it operate more efficiently.

RD: Our members are legislation scholars that teach at law schools throughout America. They have a really wide range of work that touches on areas like quantitative analysis of legislative process, judicial decision-making, etc. Some members do more theoretical, abstract, or philosophical work. For instance, I work in statutory interpretation, drawing on work in philosophy of language. There’s a huge spectrum in terms of methodological approaches within the section. Personally, I think this is exciting because there is great intellectual diversity in terms of approaches being applied then to serve similar subject matter. From this, there has formed an interdisciplinary community.

BS: In addition to the methodological diversity, there is also subject matter diversity among our members. Many of our members are focused on legislative dynamics, political theories of legislative control, and the political process at the federal level, but we also have scholars of election law, civil rights law, and the separation of powers. Our membership is diverse along both the methodological and substantive axes, which is exciting to have in the section.

RD: We had two programs at the Annual Meeting. One of them was the New Voices Program, which we held in conjunction with the Administrative Law Section. This was a neat opportunity to have distinct groups of scholars come together and have an exchange with an opportunity for feedback from senior scholars to younger scholars. Additionally, we held a program titled “Is Congress Legitimate?” In this program, we raised foundational questions about the democratic legitimacy of our legislature, which is increasingly a topic of a popular discussion, certainly surrounding issues like voting rights, partisan gerrymandering, and disproportionate representation in the Senate. The goal of this program was to give scholars within the field the chance to debate these foundational issues. We wanted to debate whether the flaws in our congressional system really require a fundamental rethinking of our approach to legislation in this country.

BS: One thing that was exciting about this meeting was the virtual format. Although challenging in some ways, the virtual format did allow for expanded participation, including, for instance, by senior scholars who might not have otherwise been able to participate in the New Voices Program. It also allowed access to the program for those who might not have been able to obtain funding to travel in person.

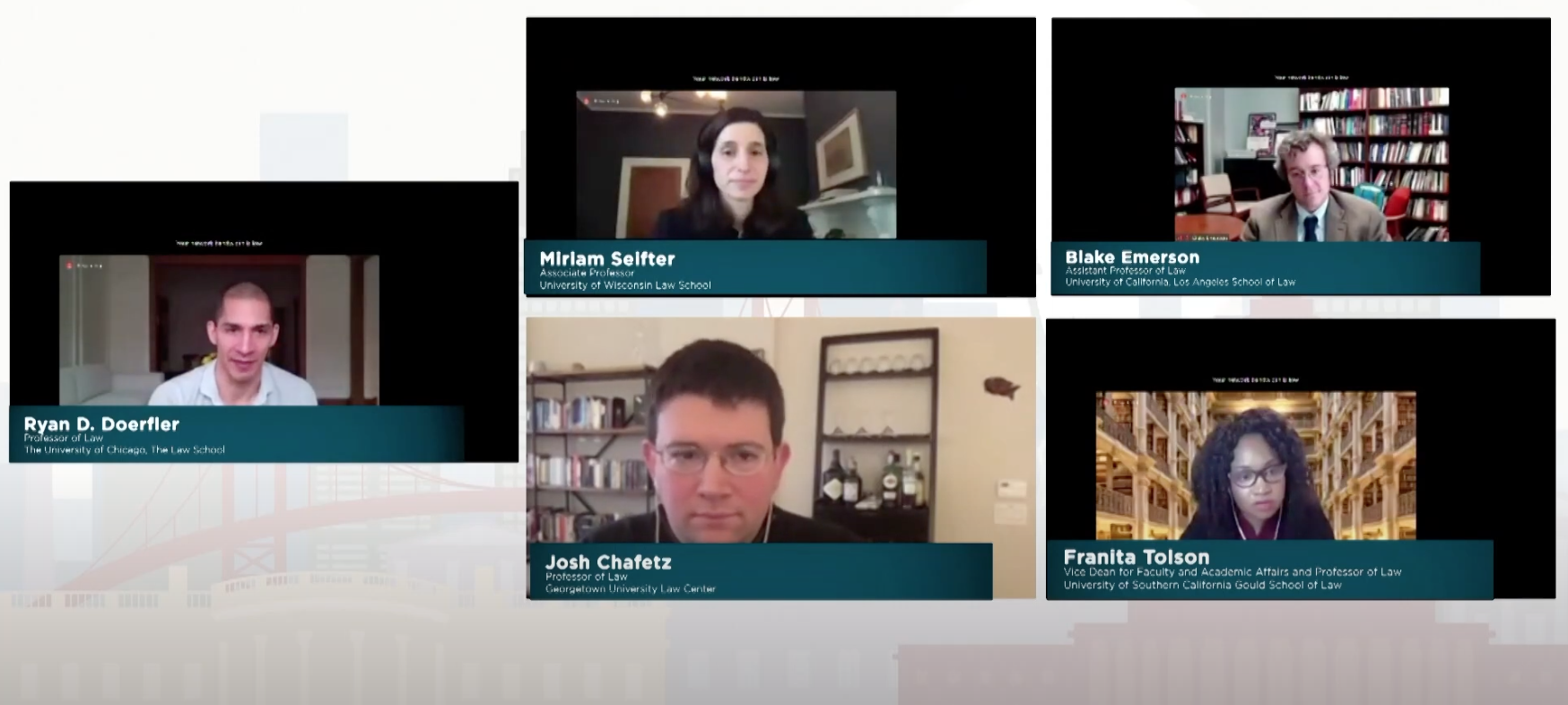

Section on Legislation & Law of the Political Process session at the 2021 AALS Annual Meeting.

RD: Legislation scholars make up a really wonderful academic sub-community within the broader legal academic community. Through various conferences and remote interactions during the pandemic there has been a lively atmosphere. This has been exciting because it brings together people who work from so many different methodological backgrounds and such a wide range of topics.

BS: Like many other sections, we are in transition. Looking forward, there are some approaches that we’re considering to increase interaction, participation, and communication among the members outside of the Annual Meeting. This could be achieved through tools such as more informal virtual gatherings or the addition of a mentorship program. In addition, I would love to build in more conversations around the impact of race on internal congressional dynamics, the legislative process, etc.

RD: I think these types of conversations would emphasize the diversity you see within the section more generally. Diversity is really valuable because it’s such a broad subject area, and there are various sub-communities, whether it’s gender, race, etc. What’s really nice about legislation community because there is such a wide array of topics and methodologies is that the groups that come together are far more diverse along demographic lines than other academic areas.

RD: To get involved in programming, I think it is good to reach out to current members of the executive committee. We try to solicit and invite people to help out with the New Voices Program, whether it’s in an organizational capacity, an accommodating capacity, or as participants for junior scholars. We know that the people involved on the executive committee are very busy, so we are very grateful to people who want to be involved and spend their time doing work for the section.

BS: We welcome ideas from people for programming, both for the Annual Meeting or outside of the Annual Meeting, that would be beneficial to them or that they’d like to see the section get involved in, or for cross-pollination between our section and other sections. We have worked with the Section on Administrative Law not just this year, but also in the past, and we would invite the chance to work with other sections as well. More generally, members of our and other sections that would like to engage further with our areas of interest should not hesitate to reach out.

BS: I don’t think it’s affected the process enough. For example, there have been iterations of legislation passed to support people’s economic needs, and Congress continues to pursue this goal with gusto. In contrast, there is not much of a centralized or even a piecemeal effort from the legislature to contribute to the improvement of racial equality, racial justice, and racial violence. My hope is that there will be some concerted effort among legislators to issue not only marginal legislation having to do with very specific areas that impact racial parity, but also legislation or practices that can be implemented across agencies in a more universal way. We need a concentrated and cross-cutting response, like Congress’s response to the economic needs arising from the coronavirus pandemic.

RD: The most striking thing is really the lack of response and the lack of reaction to the economic inequality concerns or racial inequity concerns. At the height of the George Floyd protests, it seemed like there might be a moment where elected officials would feel sufficient pressure to respond in a meaningful way, but the strategy really seems to have been just to try to wait these things out and adjust as little as officials can get away with. Given this, I’m not terribly optimistic about the short-term future. I think, especially just given the outcomes in the Senate, even with the Democrats winning the runoff elections in Georgia, given the individuals occupying the marginal seats, I’d be very surprised if we saw meaningful legislation, either to address economic inequality or racial injustice. This then becomes more of a long-term project where it falls on activists to keep that pressure and hopefully make formal progress over time.

BS: Like other areas of law, issues of race have always impacted legislation and the political process. The current moment provides an impetus to consider how the various legislative dynamics of interest to our section are impacted by racial disparities. On the one hand, those who research and write on voting and election rights, and on civil rights law, have been shining a light on the intersection of legislation and racial subordination for some time. On the other hand, other matters concerning both the impact of race on Congress, and of Congress on race, could use more attention. Pursuing this work could involve uncovering and identifying the theoretical and practical implications of institutional design shaped by racism, confronting biases that are built into systems, evaluating the differential impact of legislative processes, and scrutinizing intra and inter-branch dynamics that involve Congress and impact people of color. There has been great work by the members of our section and the rest of the AALS community, but there’s still much more to do. I hope to work those conversations into future programming at the Annual Meeting.

RD: I think maybe the most striking thing with the legislature is the absence of remote work despite so much of the country shifting to remote. The adamant refusal of members of Congress to engage in remote work has created some really stressful dynamics and opportunities for gamesmanship and worries about whether members come in to vote or things like that. In terms of Congress, it seems like the pandemic conditions created chaos in terms of the legislative process.

BS: There’s a scholarship in administrative law on the ways that artificial systems and artificial intelligence might not only impact governmental and private stakeholders and even replace bureaucrats, but also transform the processes and outcomes of administrative law. Perhaps now is a good time to consider the same in legislative processes and other intra-legislative dynamics.

As Ryan has said, we have seen such chaos, in the transition, or lack thereof, of the legislature to remote interaction. This is a good moment to figure out what would it mean to transform systems, communication, oversight, and control in order to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the legislature, particularly in light of the new requirements of “virtual lawmaking.”

RD: When you compare the legislature to the Supreme Court, which is notorious for not wanting to increase public exposure and transparency, the judiciary has still shifted to a virtual format, which has allowed for greater public accessibility. Oral arguments are now online and are universally accessible in real time. The pandemic has caused some structural changes in some seemingly more conservative institutions in terms of transparency that have not been seen in the legislature.

BS: I think the assumption is that acting remotely or acting virtually will increase transparency and access. However, we haven’t seen an increase in transparency in the legislature, necessarily. This may be because of the personal capacity of members of Congress, some of whom are uncomfortable with the technology, or it may be due to institutional or systemic factors. There are also many avenues that the legislature could take to involve the public in processes as a result of the fact that things are moving online. There is potential for more public involvement, but it has not happened yet.

RD: Substantively, the thing that’s changed the most for me is that we are in a time of transition in many ways. I spend a lot of time on statutory interpretation, which was one of my areas of research. With that, the norms are shifting in real time. It’s just as the membership of the Supreme Court changes going from a more liable methodological divide on the Court to much more eclecticism. Similarly, I spend a lot of time dealing with the interaction between both legislation and the administrative state. The Chevron Doctrine used to govern how courts would deal with agency interpretations of statutes. My course used to be structured around the intricacies of the law of Chevron. Now, it’s very hard to know what the law is at this point. I think in many ways it’s gotten harder to teach in these areas because the law is a lot less big than it was even just three or four years ago.

BS: I teach administrative law and criminal law, and some topics in immigration, and matters of statutory interpretation are prominent in both those areas. Indeed, I still focus some of my introduction to administrative law course on Chevron. It remains fundamental, and hasn’t yet been overturned. And yet, in the past I was fairly comfortable telling my students that there would be a moderate Chevron doctrine in place for some time, but now I’m not so sure. Scholarly and judicial views regarding the constitutionality and the functionality of the administrative state have become more intensified and polarized, even in just the relatively short amount of time I’ve been teaching. It will be interesting to see whether we’ll find a balance or whether this and other fundamental precepts—for instance, the nondelegation doctrine—will be altered completely in the near future.